Why We Understand History Through Accounting Books

When historians seek to uncover the secrets of a city, culture, or even an entire civilization, they often turn to an unexpected source—accounting books.

These documents are typically the best-preserved records we have available, offering a glimpse into how commerce—and, by extension, society itself—operated centuries or even millennia ago.

Given that materials like clay tablets, parchment, paper, and ink were scarce and expensive, only a fragment of information was considered important enough to record. And that fragment—as historians jokingly admit—was almost always about money.

Bills and receipts provide valuable insights into economic conditions, revealing labor costs, the prices of goods and services, and the dynamics of commercial relationships between merchants and their customers.

Lists of imported exotic goods can uncover ancient trade routes, alliances, and rivalries, painting a vivid picture of our past.

Perhaps centuries from now, historians will sift through blockchain ledgers and digital invoices to better understand our contemporary world.

Accounting on clay

Ancient Mesopotamia—found in modern-day Iraq—is widely acknowledged as the cradle of civilization. Mesopotamia was home to pioneering cities like Uruk (founded around 5000 BC), Ur (3800 BC), and Babylon (1900 BC).

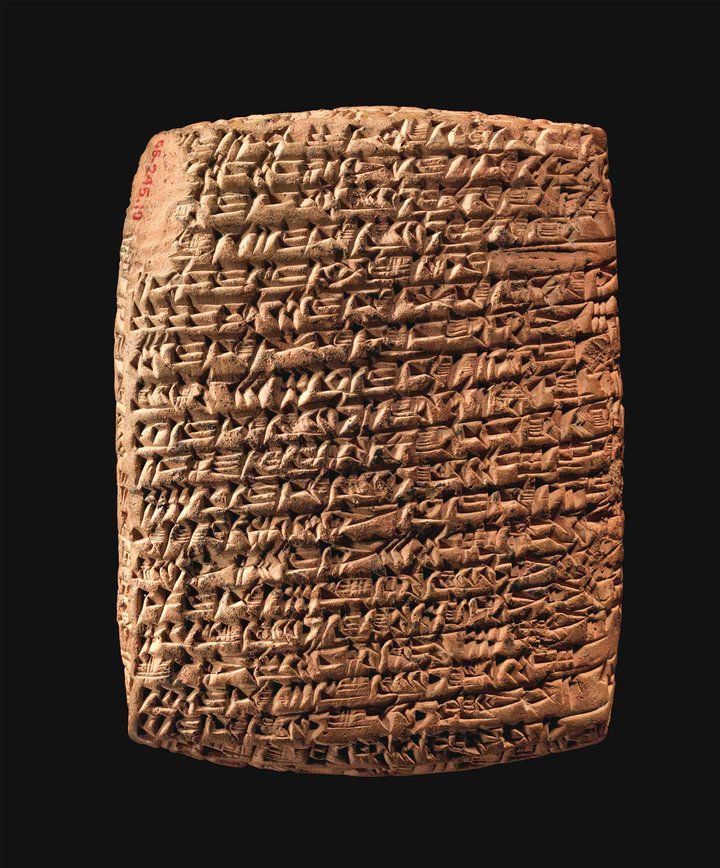

Mesopotamia developed one of the world's earliest writing systems—cuneiform. The script was crafted by pressing wedge-shaped impressions into moist clay tablets that were dried or baked to preserve their contents. Remarkably, most tablets discovered are actually detailed economic records.

Denise Schmandt-Besserat, a French archaeologist credited with deciphering many of the clay tablets, offers the following picture:

Picture the world's first accountants, sitting at the door of the temple storehouse, using little loaf-shaped tokens to count the sacks of grain as they come and go.

The archaeologist even suggests that the specially shaped clay tokens were used to count the commodities they represented, such as bread loaves, sheep, and jars of honey.

A particularly notable tablet is the now-famous Complaint Tablet to Ea-nasir, dating back over 3,700 years. Ea-nasir, a merchant selling copper, preserved this complaint at his house.

On the tablet, Nanni—Ea-nasir’s customer—accused him of delivering copper of inferior quality. This clay tablet holds the Guinness World Record for the oldest documented customer complaint.

Illuminating the Dark Ages

The medieval period in Europe (approximately 5th to 15th centuries) is often labeled the “Dark Ages” due to its cultural and intellectual decline. Despite limited written documents, financial records offer rare glimpses into this medieval society.

In Europe, which operated under the feudal system, numerous records pertain to the collection of fiefs—fees paid by vassals for the right to utilize land owned by their feudal lords.

Since the Catholic Church was a dominant societal force, surviving records also reflect clerical finances. Covering everything from costs of church construction to tithing, a mandatory tax of one-tenth of one’s personal income.

Failing to pay the tithe could lead to excommunication—a severe penalty in an era when church membership profoundly influenced social and political life.

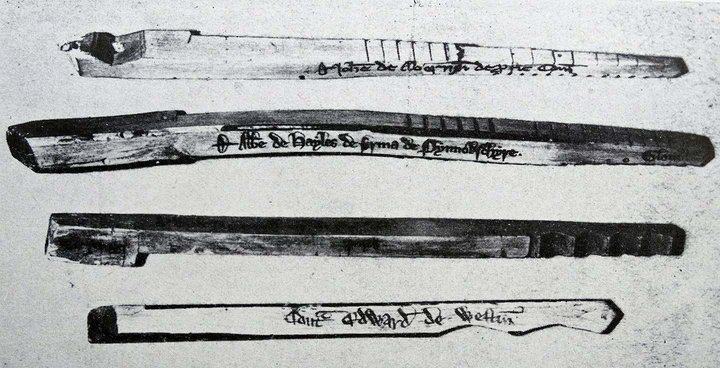

An honorable mention goes to the tally stick, a practice popularized in 11th-century England. When two parties entered into an agreement regarding a loan or debt, they would inscribe the terms onto a wooden stick, which was then split into two halves—one retained by the debtor and the other by the creditor.

Due to the unique grain of the wood and the irregular edge created when broken, the authenticity of each half was unquestionable. The two pieces were known as the “foil” and the “stock,” the latter term still used today to refer to shares in a company.

The Medici family's innovations

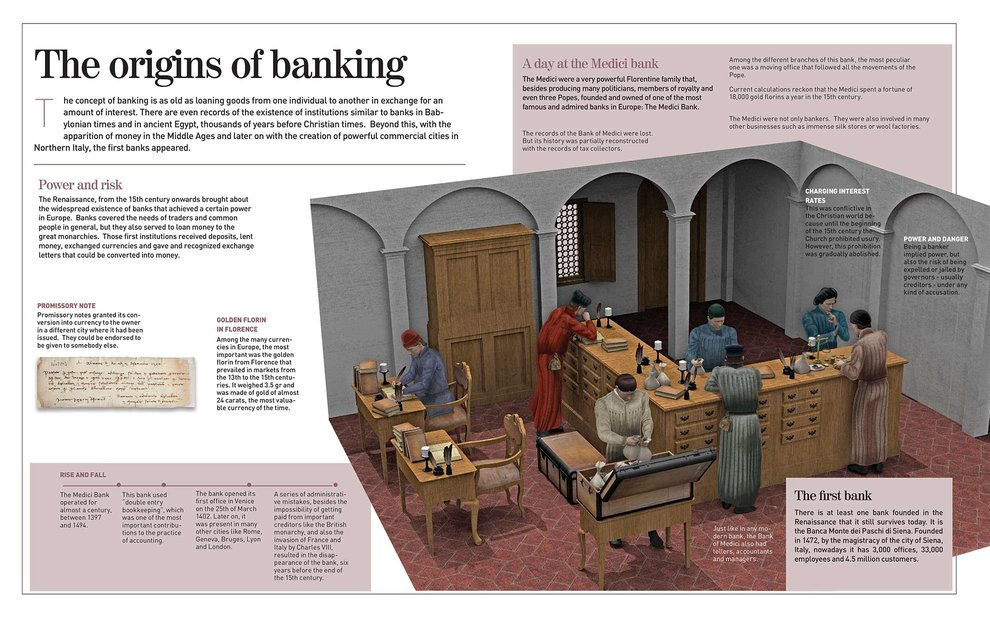

The Renaissance, spanning roughly the 14th to 17th centuries, marked profound advancements in science, exploration, art, and commerce. Maritime exploration, which brought unprecedented trade opportunities, demanded more sophisticated financial tracking.

In response, the method known as double-entry bookkeeping emerged. This system records income and expenses separately, clearly distinguishing assets from liabilities and revolutionizing financial management in the process.

No family exemplifies Renaissance-era finance better than the powerful Medici family of Florence, Italy. Their bank, founded in 1397, became Europe's largest financial institution of the time, with branches extending to Rome, Venice, London, and Bruges. The Medicis' meticulously maintained ledgers reveal their immense economic power and far-reaching political influence. Several Medici family members even became popes.

The Medicis further distinguished themselves by pioneering banking practices that remain fundamental today, including the widespread use of letters of credit—documents allowing merchants to trade securely without transporting large amounts of cash. By reducing the risks associated with long-distance trade, these financial instruments greatly facilitated international commerce.

Colonialism: commerce and the tragic cost of trade

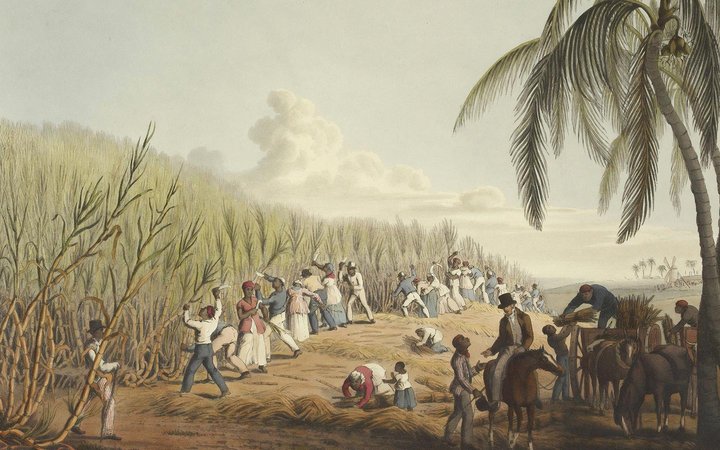

With global exploration accelerating in the 16th century, European powers established extensive international trade networks. Detailed accounting records help historians unravel which nations dominated commerce, what commodities were highly valued, and how economies were shaped by trade.

Surprisingly, historians have concluded that England's international trade during this era was actually a net loss for the country.

However, the establishment of the East India Company in 1600—a powerful organization with a monopoly on importing goods from Asia to Britain—laid the groundwork for modern business practices, influencing how ambitious entrepreneurs today frequently opt for joint ventures rather than pursuing business endeavors independently.

The Colonial period also saw a rise in the slave trade. Chilling accounting records of transactions involving enslaved people provide insights into the economics of slavery—prices, numbers, and conditions endured—serving as a stark reminder to ensure history never repeats itself.

Today's invoices: history in real time

Let’s fast-forward to our digital age. Ecommerce and instant payments necessitate sophisticated accounting systems capable of managing constant, real-time financial transactions.

Today's businesses and consumers demand comprehensive documentation, from purchase order references to standardized international trade terms (Incoterms). Sufio is a leading company that illustrates this modern trend by automatically generating invoices from Shopify orders and sending them to customers.

On the customer side, e-invoicing, or automated invoice processing, is coming into play, requiring invoices to contain the invoice data in a machine-readable format.

The digital invoices we create today may serve as historical “artifacts” for researchers in the future.

Peering into the future: blockchain and beyond

Cryptocurrencies, despite their uncertain future as universal payment systems, have introduced a transformative technology—the blockchain.

In simple terms, the blockchain functions as a decentralized, transparent ledger recording every transaction in a given cryptocurrency. Rather than individual records kept by banks, the blockchain's publicly accessible and immutable ledger provides unmatched transparency.

There's a good chance that, centuries from now, historians will decipher the modern world through blockchain ledgers and (hopefully) even Sufio's own digital invoices, both of which should be easier to work with than old clay tablets or withering parchment.

Professional invoices for Shopify stores

Let Sufio automatically create and send beautiful invoices for every order in your store.

Install Sufio - Automatic Invoices from the Shopify App Store